In my preparations for a megadungeon game I have among my list of Play-by-Post (or, hopefully, in real time whenever possible) campaigns I need to get out of the ground (heavily influenced by Lost Carcosa from my friend Tristyn), I gave consideration to what I want out of that, aesthetically and creatively. A game that doesn’t speak to my worldview and artistic interests is not one that I should be running.

So I set a few goals that would keep me busy and entertained both during preparation and the actual game. I gave consideration to megadungeon theory and referred back to Philotomy’s Musings, which still lays the ground of my approach to D&D as a game.

The Goals

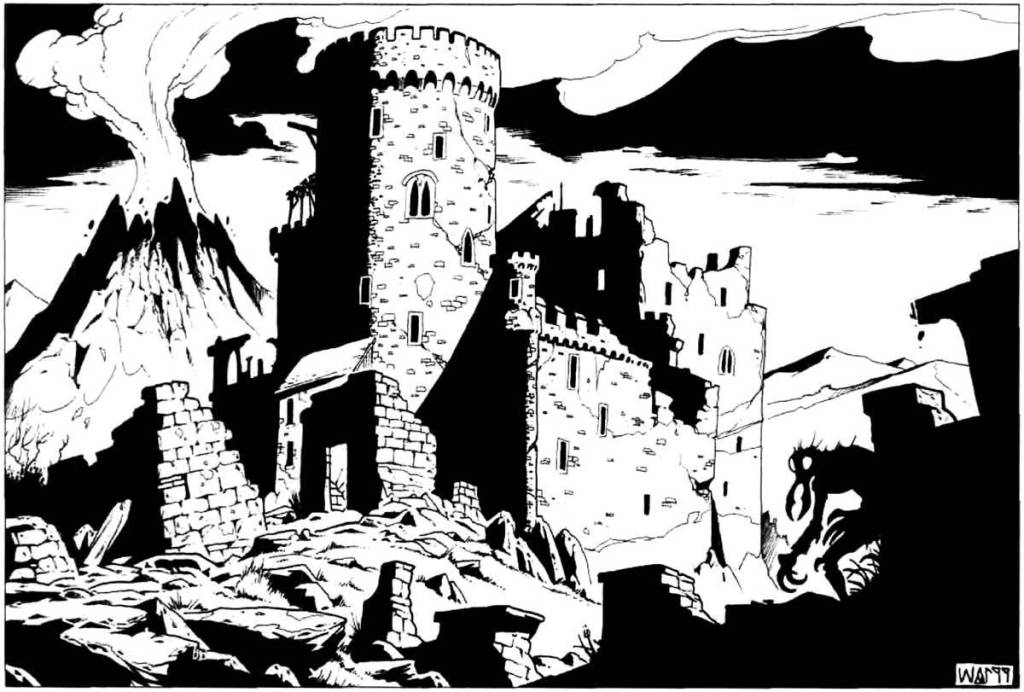

To create a megadungeon campaign, defined as not just a campaign where there’s an infinite tentpole dungeon the players can go into when they aren’t sure which threads they want to pursue, but that is the bulk of the game.

Therefore, the campaign must be thought in a manner that other gameplay modes aren’t just kept rather aside, but that their benefits are brought as close as possible to the central exploration loop of the dungeon such that separate modes of play aren’t strictly necessary to be considered in long-term.

This also comes from my need to uphold the fundamental human virtue of laziness as my guiding principle, and therefore devise a structure of play that can seamlessly integrate the external faction play into the dungeon without forcing me to consider too much at once, nor to make the urban spaces an abstract thing without its own logic that exists merely to sell wares and rest.

To make it a Mythic Underworld which keeps being a threatening, alien environment of hate and abstraction, without making it an exceedingly gamey concept that seems at odds with verisimilitude.

While smaller dungeons can uphold those principles and just be places of strangeness without straining credibility, Mythic Underworld megadungeons can very clearly feel as spaces that exist only for the sake of the game, rather than part of the world where we are gaming. They are prone to feeling unlike a living, breathing space despite its aspects as a genius loci because they lack consistency with the external world. This is a feature, not a bug, in many tables. Those who lean in supernatural horror and aim for a basic sense of the tactile, like myself, must find a way around it somehow without integrating its concept of ecology to the macro-ecology of the campaign.

I’m uninterested in large naturalistic dungeons, nevermind a naturalistic center of long play. So the Mythic Underworld proposal as assault on rationality appeals, but it must be constructed in a framework of rationality for best impact.

To make such a dungeon functional with creatures existing as individual nightmares instead of organized factions, given that faction play inside the dungeon is fundamental so the whole game can work and this approach is nearly Quixotic. The internal faction play is the reason to have a megadungeon, and the lack of faction play is a surefire way of making it unplayably boring. Smaller dungeons already suffer without factions.

However, internal dungeon factions would both bring naturalism that isn’t my intention and make it so that the monsters are, on some level, less hazards, less forces of (un)nature, less like Dwellers.

The Proposal

This hypothetical megadungeon lacks internal factions. Monsters are unique creatures, acting as manifestations of this hateful place’s eldritch sorcery and supernatural terror, and aren’t interested in such concepts as politicking. In other circumstances, such a proposal would be doomed to immediate failure (and might as well be!), but my solution is rather simple: the bulk of the encounter tables are rival adventure parties from other town factions, all trying to explore the place under the command of patrons. The megadungeon factions are merely the factions of the external world, erasing distinction between modes of play and spaces.

This aims to make the elusive concept of the rival adventure party less of a gimmick. The active Referee has to manage the world with an eye towards the many factions in town, wilderness and every individual dungeon, the fluctuations of the economy, the passing of time and restocking of areas, the reasonable conclusions of how those processes came down in the fiction, and many dozens of other issues. Rival parties being the most active figures the players will face, since monsters are such a rarity during exploration, makes that particular concept more smoothly integrated into the concerns. After all, considering the number of potential PCs that exist in the game, plus the wild west and frontier aspects of D&D, and therefore how many adventurers there might be in the world, an absence of rival parties is more conspicuous than their inclusion in games.

While we have developed tools to deal with rival parties as an active part of the game, such as deploying Clocks and such, it is another exterior factor to track during prep between sessions and applying directly in the moment.

Rival parties are the faces of town and nearby factions, which solves three issues. The first one is the need of tracking faction play outside the dungeon as well as inside. Now the very act of exploring and encountering others inside the dungeon can bring immense and immediate consequences to external faction play without having to track a domino of influences. Restocking, too, can be interpreted either as the Mythical Underworld fucking around, or as the direct result of other adventure parties meddling, which can be a good hook for negotiations and receiving requests from patrons about lost rivals, missed objects and the like.

The second issue is keeping one of the main draws of megadungeon play (faction rivalry and politicking) while keeping it a conceptual horror space. Indeed, its most disturbing qualities can very easily be displayed by the remains of other adventurers and rumors that the players get directly, perhaps from people they had seen just recently, as they rush deeper and deeper into the nightmare. Which is what my ideal of dungeon fantasy lately shifts towards: spelunking as tragedy.

The third issue, related to that, is the megadungeon assuming characteristic of a thematic object that represents the larger political “game” patrons play with their servants and mercenaries lives, with ties nicely to the very game-y, “it’s here because we are playing D&D” nature of the Mythic Underworld megadungeon while granting it symbolic and literary qualities, which pleases me immensely. It is a game space, yes, because it’s the focus of the game of thrones at large. Having the megadungeon as the center of power acquisition for factions also means that it suddenly has a naturalistic context inside the game’s purposes without it being a naturalistic space in itself: it doesn’t matter that it is an absurd, wargame justifying space of unhinged dark magic that has little “macro-ecology” with the rest of the world (the famous “a mad wizard built it, now go down there”) if the players can lean into the web of relationships around it, and facing their own personal ambitions regarding it, as their firm human and realistic framework to comprehend the beast. The megadungeon is understood different without needing a realistic ecology.

While such thoughts predate my analysis of Campbell’s presence in Moldvay, it is amusing how much this proposal matches my prediction for the urban game in the speculated Campbellian campaign. The hostility of the urban space is represented as the slow but inevitable continuum between dungeon trauma and the social consequences outside.

While such a megadungeon model doesn’t deny the presence of demihumans and other character types in the campaign, it seems best inclined for a human-only condition both for its aspects of supernaturalism and the need for groundness.

A note on mechanics: reaction rolls inside of the dungeon are directly connected to the social standing with the factions outside, so we can quickly gather what bonuses are depending on the players’ standing with the factions in the outside world. Reaction rolls for monsters follow the LBBs principles outlined in my Demesne suggestion for their alienness.

If anyone has previous theory on this they could share with me, I’d be immensely grateful.

I found this idea VERY intriguing, but while thinking it over I also raised a number of questions. I love the concept of rival adventuring parties, but certain issues seem to complicate the execution for me. I’ll briefly describe my questions and issues in case they help you hone your thoughts on this approach. 🙂

+ as equally-intelligent and -competent adventurers, encountered rivals should be able to offer (if they want to) very coherent discussion of just how they got there. Even in a “Jacquaysed” dungeon with many paths (or especially in such a dungeon?), every appearance of a rival party that doesn’t have a hostile reaction might lead to questions like: which path did you take to get here? What can you tell us about it? (So far, that might all be well and good, but…) Why are there still monsters and treasures left along the path you traveled? Etc. There may well be an easy fix that I’m overlooking, but I sometimes scratch my head over the most elegant way to handle this without increasing my own workload.

+ faction play really shines, in my opinion, when the factions are driven by concrete goals, situations, and access/blockage to specific assets. I love the oft-quoted idea that Faction X has Goal X, but faces Obstacle X, and so they will Plan X.” You have raised a number of ideas about factions warring, scheming, or whatevering for the resources in the dungeon – and I really like the idea of that – but I still think you need some sort of context outside the dungeon with verisimilitude to make this idea work, at least well.

+ will external factions start building bases and seizing real estate inside the dungeon? Unless the mythic dungeon’s ecology somehow prohibits this, it would be a logical step, which might lead (ooh, “diegetically”) to dynamic new situations inside the dungeon. Hmmm.

Finally, a post of mine from a while ago leans rather in the opposite direction but might be seen as a way to tackle somewhat similar concerns.

https://gundobadgames.blogspot.com/2022/05/dungeon-extraction-posse-vs-chaotic.html

Cheers and thanks for the thought-provoking read.

LikeLike

Thank you for the kind comment (and your post is very interesting!) There’s some unique challenges here that demand extra prep in other areas, although I suspect by the end will be just as much prep as the regular megadungeon, if just a bit more for smoother play later.

Instead of focusing on drawing the first three levels of the megadungeon as a whole and then lightly sketching a town and beyond, this campaign would require a very precise sketching of external factions so as to fill the encounter tables. I like that in the process (most likely handled directly by the restocking procedure, although only experience will tell if an extra rule is necessary) the external factions will create their own base inside the dungeon in an organic way and, in a certain way, fulfill the promise of monstruosity suggested by the setting by taking the role of monster factions (especially if some groups just split from their patron and become thralls of the dungeon).

As for how the treasure and occasional monsters are still there, that’s the most pressing issue (and can often be an issue in regular campaigns as well). From a campaign start framework, the megadungeon would have to be a very recent thing to justify not have been cleared yet by the many adventurers.

As for why they would leave things behind, or not pick them up, we have a field that partially would demand improvisation according to the specific situation. Sometimes you can explain stuff as “we met another group and both retreated to not die”, or “we ran from a terrifying thing”, but you can’t say that every time without it becoming trite. Many ways of explaining it will certainly be improvised, but we need a solid base so we can fall back as required.

The obvious, even if brute force solution, is that the malevolent dungeon keeps generating treasure to make conflict worse and amuse itself. I don’t like this solution, at least at first, for a couple reasons. It goes back to the inherent gamey-ness of the Mythic Underworld in a way that strains the verisimilitude that the whole framework brings to the external world and how the dungeon connects to it. It raises the question as to why adventurers would even go down to lower floors and face more danger if the resource isn’t more scarce (an elaborate procedure regarding how value decreases and tracking the dungeon willingness to generate that treasure if more people don’t go down could be created but I want to avoid that if possible).

Outside that, the most obvious answer would be that other adventurers are bumbling idiots, which we have to discard immediately if the game is to be even a tiny bit convincing. The possibility of NPCs being possessed by the dungeon and more likely to leave things there is… cheesy and lazy in a way that doesn’t match my laziness. The concept of specific factions wanting extremely specific things from the dungeon, and leaving treasure outside that objective behind, is one that can tie back to the framework nicely but is also heavily dependent on specifics of the campaign instead of something we can broadly apply. The number of competing factions also greatly influences any approach.

It’s a challenge that I gave thought to and still can’t find a general answer outside relying on restocking and context… which in a theory field can be enough until actual play starts. We will see.

I’m not ignorant to the fact that maybe this sort of approach works more smoothly in an agenda different from the wargaming ethos of adventure gaming (I think the premise can make for a kicking drama-focused game, as Heart: The City Below), but it appeals to me verifying how well it can work as an adventure game regardless. I think there’s the seed of a great O/NSR style campaign here, but only playtest will tell.

LikeLike

I was thinking about this more last night. As it happens, the next phase of my campaign requires somewhat parallel design choices (not a megadungeon, but a whole ruined city with a chaos-twisted underworld beneath). For various reasons, I am currently thinking about checking out Emmy Allen’s depthcrawl titles (The Stygian Library and the Gardens of Ynn) and perhaps harnessing much of that content to save me time.

In case you aren’t familiar with the core idea, the ‘depthcrawls’ provide materials for developed, interesting rooms and encounters, but the exact spatial relationship and connections between those rooms is not specified – instead, you procedurally generate which room is encountered next via a simple analog formula, in play.

Thinking about this, it occurred to me that something similar might help your situation, so long as the core conceit doesn’t bother you. If you’re happy with a very mythic, magical, or even chaotic underworld, then you might accept that the nodes within the underworld are fixed, but the paths among those nodes are always shifting in madcap ways.

This means you can prepare rooms to your heart’s content, but the exact navigational path between rooms may change every time you go into the dungeon. And THIS means that whenever you encounter a rival party, the path they took to get here could have no relation at all to whatever path YOU would have to trace to find the rooms they went through.

This would allow engagement with the designed rooms, engagement with the wandering adventuring parties, all the faction-relationship stuff you want, and abstract/handwave away the spatial relationships between dungeon rooms.

Might that idea appeal?

LikeLike

Funnily enough, one hour after posting my comment, I gave consideration to depthcrawls but also Flux Space as being the possible approaches to it (if I were using a dramatic approach, Jason Cordova’s Labyrinth move would be the obvious choice), and you laid out exactly the reason.

Unrelated to such practical concerns and moving towards setting, I can see this megadungeon model being particularly conductive to contemporary fantasy games as to how transportation and communication can bring a very interesting variety of factions and make the megadungeon look even weirder in contrast to the everyday.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, flux space could be useful here too!

If you don’t mind me throwing a couple more of my own older posts at you, I’ve mused on flux space and megadungeons before. See (especially the second half of) this old post:

https://gundobadgames.blogspot.com/2020/10/mad-musings-on-streamlined-mega.html

…and maybe this one too:

https://gundobadgames.blogspot.com/2020/10/abstract-vs-pointcrawl-navigating-in.html

LikeLike

I will have to give a more in-depth reading and comment later, but first I want to thank for the posts (I can see that they will give me a lot to think about), and share the funny coincidence that yesterday I was talking with a friend about dungeoncrawling with Cthulhu Dark in a manner separate from Trophy (which I admire but ultimately do not mix with much for the reasons you stated), so maybe that’s a future blogpost!

And coincidentally Trophy Gold was in my mind today because of how Hunt Rolls work (in a similar manner to Cordova’s Labyrinth) and how they would meet the desolate megadungeon in a dramatic agenda, but ultimately not work for wargamey OSR play. Still, interesting to think about.

LikeLike